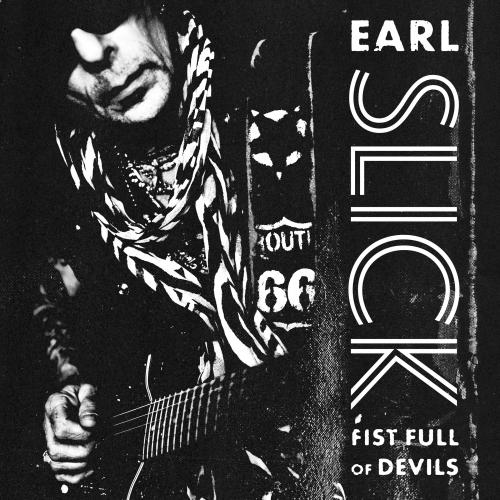

Earl Slick has a “Fist Full Of Devils”

Guitarist Earl Slick never had a Plan B. Still doesn’t. In fact, he doesn’t believe in backup plans.

“If you have a backup plan,” said the guitarist who for decades worked alongside rock royalty including David Bowieand John Lennon among others, “then eventually you become the backup plan.”

Which explains -- and fuels -- Slick’s new album, “Fist Full of Devils.” Harnessing his musical roots as a child of the 60s when blue-based rock pushed its way to the front of the line and incorporating his decades as one of the most sought-after touring musicians in the business, Fistful is Slick as he’s been from the start: an artist who fully mines the depths of the blues and guitar by drawing on a toolkit assembled from blues to glam to punk to rockabilly.

Released on England-based Schnitzel Records, 2 July 2021, the 11-track instrumental album is no retread retrospective of Slick’s run of 40 years as a professional guitarist; it’s an audible demonstration of a virtuoso still pushing deep into rock and roll’s blues roots.

The album, Slick says, is acrobatics without a net. He’d have it no other way. From the moment he picked up a guitar, “I’ve never wanted to do anything else.”

Early Life

Born Brooklyn, New York in 1951 as Frank Madeloni, Slick said there was no better period for a musician to arrive on the planet. “I was born in Brooklyn at exactly the right time.”

Laced with nightclubs, recording studios and loaded with local talent, New York in the middle 20th Century was a cradle of American music. But the specific reason for Slick’s happy accident of birthplace would arrive 13 years after he did.

Like so many American children of the middle 1960s, Slick remembers precisely what he was doing on Sunday evening at 8:12 EST, Feb. 9 when he was 13 years old. That was the night the Beatles first appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show. A record 73 million Americans had tuned in.

The next day at school, he said, every kid on the playground wanted to form a band. No one had any gear. Or any skills. But everyone now wanted to play.

It was 1964 and it turned out Slick was living right at the beachhead of the British Invasion.

The teenager began pestering his dad for an electric guitar. The family didn’t have much money and moved frequently to find successively cheaper rent in Brooklyn. Still, his father scraped together $30 for a bargain Danelectro guitar.

Recalled Slick: “I began noodling with the guitar but that wasn’t going anywhere. So, my mom got me lessons.” That only lasted three sessions. “I was playing along with these silly, nursery rhyme kind of things like “Oh Susanna” or whatever the fuck.”

Playing guitar, Slick thought, wasn’t supposed to feel like school. And he hated school. So Slick quit lessons and spent all the money he could earn on blues records. He’d sit in front of the stereo for hours, moving the needle back and forth to transfer those grooves into sonic and muscle memory. “It’s all I did. All I thought about, “ he remembered.

Then came the breakthrough that locked the guitar into his hand for good: The Rolling Stones. Slick loved the Beatles’ music but the first time he heard the Rolling Stones – scruffy, harder-edged, deeply blues influenced – he knew what he had to do.

“Your parents might accept the Beatles. They’d never accept the Stones. So I loved them. It’s like the world went from black and white to technicolor.”

“From the Rolling Stones, I learned the blues.” Sifting through the Stones, Slick discovered Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon. Chuck Berry, Buddy Guy. The 12-bar blues chord progression replaced schoolwork.

When Slick and a couple of friends “got good enough to get out of the bedroom with the amp,” they began piecing together cover songs, Louie Louie, Walk Don’t Run, Little Red Riding Hood.

The friends started with basement parties. “Two guys sharing an amp,” he said. “We only knew bits and pieces of songs.” If you wanted to graduate to high school dances, you needed memorize 15 songs, he said. “This meant you’d play your set list through several times a night.”

The repetition meant practice and polish. And money. And soon, his group were regulars on the high school dance circuit. But Slick wanted more. And New York in the late1960s offered plenty.

The pivot to pro

Credit New York state and relaxed liquor laws for Slick’s early career path. The drinking age was 18 back then, not 21. He was 17 and he and his bandmates got phony IDs. They only had to look 18, after all. Then they could play in the bars.

“When I started playing guitar and where I started playing guitar in New York City – unbeknownst to me at the time – I was in one of the major hotspots on the globe if you wanted a music career,” Slick said.

The Golden Disc in Staten Island, open only one night a week. Sonny’s Lounge. Elleanor Rigby’s. The Swiss Chalet. In most places, bands played five sets a night, 9 PM to 4 AM. He and his bandmates began venturing into Greenwich Village.

Slick was 20, when the creator of the New York Rock ‘n Roll Ensemble, composer Michael Kamen, recognized Slick’s talent and brought him into the studio for collaborations with established pros such as David Sanborn, and Hank DeVito and Paul Butterfield.

“Michael took me under his wing,” Slick said. “And eventually he put me in his band.”

But initially only as a roadie. Slick laughed at the memory. “Michael said, ‘I don’t really need another guitar player right now. We’re getting ready to do a tour. Would you carry gear?’ I said, ‘I don’t give a shit. I need to get out of Staten Island.’”

He brought his guitar along and would jam with the pros at the pre-show sound checks. One day Sanborn said to Kamen, “Why isn’t (Earl) playing in the band?”

Noted Slick, “That’s where it all started.”

Bowie and Bowie redux

On the road with Kamen and in New York recording sessions, Slick knew he was levelling up quickly. New York in the early 1970s was a rock and roll epicenter. So was London. The two tribes shared (and stole) talent and ideas.

One day, Kamen said he arranged an audition for Slick with a “really big artist” for a new gig. He declined to say who. “(Kamen) said, ‘Keep your shit together. They are going to be calling you.’”

A few days later a woman called. She said she was David Bowie’s assistant. Legendary lead guitarist and arranger Mick Ronson had left the band. She asked if Slick would come down to a Manhattan studio for an audition. “I thought there was going to be a whole band there.”

There wasn’t. Bowie’s producer was inside mixing Bowie’s eighth album, Diamond Dogs. But Bowie was nowhere to be seen. Slick was handed an amp and some headphones.

The producer asked him to play along to unmixed and unreleased Diamond Dog songs such as Rebel Rebel. He played for about 20 minutes.

“Then David walked in. I didn’t know he was there. He’d been listening from another room. He picked up a guitar and we noodled around for about an hour and we talked.”

Bowie politely said thank you and walked out. His assistant came back in and said they’d be in touch within two weeks. Twenty-four hours later, she called. They offered him the gig to go on the Diamond Dogs tour. Slick was 22 years old.

For the next two years, through the Diamond Dogs tour and the two studio releases, Young Americans and Station to Station, Slick’s playing expanded well beyond 12-bar blues. He left Bowie after Station was and formed the Earl Slick Band. He began a series of collaborations with Ian Hunter, John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

Then after the release of Let’s Dance in 1983, Bowie came calling again. Stevie Ray Vaughn, who played guitar on the album, quit the band after a dispute with Bowie. Slick was called as a last-minute replacement for the upcoming Serious Moonlight Tour.

A cascade of gigs and projects followed: He founded Phantom, Rocker & Slick which charted two top 10 singles and reached number seven on the Billboard rankings. As an added bonus: Slick’s idol Keith Richards contributed to one of the album’s singles “My Mistake.”

“That is up there with my best music moments,” Slick remembered. He was hanging out at Mick Jagger’s birthday party and ran into Richards. “I told him we were in the studio recording an album. I asked him if he would play. He said yes and then he actually showed up to play on the record! Unbelievable.”

Then in the early 2000s, Bowie came calling again. Slick played in on the next three studio albums, Toy, Heathen and Reality. He performed as the touring guitarist for the albums as well. Never accused of resting on his laurels, Slick then released another solo album Zig Zag and joined Slinky Vagabonds with original Sex Pistols bassist and songwriter Glen Matlock – a musician he will tour with later this year to support the album.

In 2015, he again worked with Bowie on his second-to last album The Next Day before Bowie’s death in 2016.

Through the decades and of the performances, the studio sessions and the many bands, Slick kept feeling the tug of the blues, the music that first opened his mind and then every door thereafter. Fistful of Devils represents that return home.

And the path home, in this case, cut through one particular Chicago nightclub: Legends, owned a man who Eric Clapton called the greatest living blues guitarist, Buddy Guy. “I was in Chicago and Edgar Winter was playing at Legends. I sat in with Edgar. Buddy wasn’t supposed to be there, and I was a little disappointed. Then Buddy walks in while I was playing. And he invited me to play.”

For Slick, that instant became of the biggest moments of an already remarkable, 40-year career. “That first night with Buddy Guy. Wow. Buddy’s where it comes from. Someone like him thinking I was good enough to get on stage with him (long pause) was a trip.”

At this point, Slick began branching out in his career, joined forces with GuitarFetish.com with a successful line of custom Earl Slick Brand guitars, straps and pickups.

Music though retained the driver’s seat. That evening with Guy pointed Slick’s compass toward his early career roots. Some of the tracks on Fistful were ideas that had been rattling around in his hear for decades. Some were wholly new. The sinister “Black,” for example, seemed to flow up from the ground when they entered studio, he said. It was written, “in maybe 10 minutes,” he said. “It’s dark.”

Contrast that with the soaring, diving number “Vanishing Point.” That was born in a lick he’d saved nearly 30 years ago and only recently rediscovered in a sound file. He didn’t know what do with it when he wrote it, so he tucked it away. But now, “all of these years later I came at it with a different head than I had then.”

And this is what people are going hear in “Fist Full Of Devils” he said: That lifelong journey from Brooklyn didn’t leave him empty handed; he brought back the prizes, the tricks, the scars, the influences and the tools from a road that never presented a detour. Or an end.

It isn’t lost on Slick that NASA broadcast Bowie’s “Life on Mars?” when the Perseverance rover touched down on Feb. 18 in what amounts to a multi-billion-dollar effort to answer Bowie’s simple question. That’s Slick playing the guitar millions of people listened to. Again.

He’s a man, after all, who knows a thing or two about persevering, about longshots and locked-in trajectories. Perseverance also had no backup plan when it was launched. It had to get there.

“I am,” Slick said. “Exactly where I should be.”