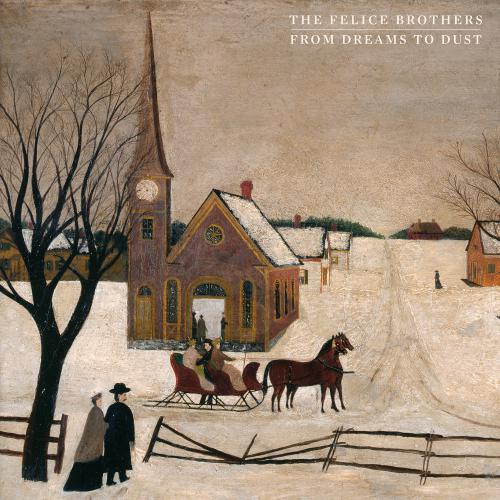

Band: The Felice Brothers

Album: From Dreams To Dust

VÖ: 17.09.2021

Label: Yep Roc Records / Bertus Musikvertrieb GmbH

Website: http://www.thefelicebrothers.com/

The Felice Brothers - From Dreams To Dust

Ruminating on the risks of taking things for granted in our daily lives, Ian Felice, the lead singer/songwriter of The Felice Brothers, expresses how meaningful the experience of playing music with his band has been after long months of social distancing. In From Dreams to Dust, their eighth and most recent studio album, out September 17th on Yep Roc Records, the band’s exuberance to be together doing what they do so well is palpable. Characteristic of The Felice Brothers, the new tracks are a mixture of somber tunes with ones that are musically upbeat, all the while carrying messages that beg listeners to think deeply about the environment, humanity, legacy, and death. Many of the songs depict the passage of time, nostalgia, transience and getting older. For songwriter Ian Felice, there must also always be a current of hope in the music.

“I want for my music to do what the best music in my life has done for me,” explains Ian. “I want to do that for other people—to help them think through hard times or think through how to communicate something they didn’t know how to; to just make them happy. This may sound ironic, because my music is kind of dark sometimes, but the music I love best is just the most hopeful music like Pete Seeger singing about humanity getting along or Michael Hurley music that connects to some childlike simplicity that makes you feel light and happy. Music is a medicine. It can make our time on the planet a little more enjoyable.”

The Felice Brothers, Ian (guitar and lead vocals) and James (multi-instrumentalist and vocals), hail from the Catskills, NY, where their early songs echoed off subway walls and kept company with travelers and vagrants. Their current lineup, with the addition of bassist and inaugural female Felice member Jesske Hume (Conor Oberst, Jade Bird) and drummer Will Lawrence (also a singer/songwriter) as their rhythm section, promises to be the best yet.

Nathaniel Walcott (trumpet) and Mike Mogis (pedal steel player) act as an accompaniment throughout the tracks, the latter of whom mixed From Dreams to Dust, which was produced by The Felice Brothers.

A folk-Americana-rock-country band with deep roots in varied genres, The Felice Brothers are what Rolling Stone lauds as“musician’s musicians” and poets. Indeed, Ian has proven his pedigree as a poet with the publication of his limited-edition collection of poetry Hotel Swampland (2017).

They are known by fans for their catchy tunes like “Frankie’s Gun,” “Love Me Tenderly,” “Cherry Licorice,” and “Lion” and, more recently, 2019’s “Undress” and “Special Announcement,” but they offer much more than a great sound. Seamlessly interweaving bizarre catalogues of literary and pop-culture references with vivid portrayals of life and its kaleidoscope of tragedies and hopes, their lyrics and dazzling musical accompaniment not only sound good but demand introspection. Some of the themes that run through their music, as Ian states, “are perennial” and are centered around “searching for something or transformation.” Others explore “characters trying to achieve some ideal they’re striving for” or who are “being weighed down by reality.”

Their latest in this tradition is their opening song, “Jazz on the Autobahn,” a piece marked by its explosive sounds that invite us to join in the merriment of the maypole in the midst of uncertain futures. The song displays Ian’s talent for switching from his smooth narrative voice to singing in his vintage, rich tone. Jesske’s adept bass strumming, accompanied by Will’s rhythmic drumming, act as a pulse, pleasantly complemented by James’s melody on the piano. Together, along with the wailing trumpet, The Felice Brothers are mesmerizing. The band’s cohesiveness in this opener and the brilliant synthesis and harmonizing of voices and instruments reflects the members’ varied talents as well as their unified vision.

Detailing the story of Helen and The Sheriff who are driving together in a “doomed Corvette,” “Jazz on the Autobahn,” Ian explains, is about a couple of people who have “left behind their entire lives in search of something but are haunted by a feeling of looming catastrophe, and the two souls are adrift in uncertain times, trying to understand their own feelings, hopes, and desires.”

As he has throughout his career with The Felice Brothers, Ian harnesses the dissonance of life to produce music that is at once musically inspiring and conceptually sophisticated. He works through the difficult realities of life as a way to, at least temporarily, end at a more life-affirming state.

“I just have strange emotions and things I don’t understand. Sometimes when I write, it helps me work through the ways I feel,” Ian explains. “I want it to be about art.” These two mutually informing needs, that of wrestling with the emotional and psychiatric impacts of living in a world saturated with tornadoes, mushroom clouds, chemical rain, poisoned bird baths, worsening markets, greed, earthquakes, and war, and creating artistic productions that offer us what Ian calls “digestive realities,” define two notable aesthetic principles that characterize Ian’s songs and all of the tracks on From Dreams to Dust.

Ian wants his songs to do for others what his favorite songs do for him, which is to help listeners get through hard times. “The greatest thing,” he states, “would be for people to be inspired by our music in a positive way.” But for Ian, doing so involves not turning away from adversities but rather requires facing harsh truths for the purpose of nourishing us with these digestive realities that might help us work productively through otherwise demoralizing and debilitating prospects. Thus, as the speaker of “To-Do List” writes a plan, or perhaps a bucket list, as “the plague goes by,” the speaker resolves to “Befriend an Unfortunate lunatic” and “Bring Flowers to the Sick” as well as absorb the light from the “amorous rays” of the sun.

The songs in From Dreams to Dustask us to pay close attention to Ian’s narrative techniques and literary devices, transforming his songs into poetry and short stories. “Ian is so good about taking poetry, novels, folk art, and a huge wealth of artistic knowledge and metabolizing those things into music that is never academic or stilted but feels so alive,” explains James on his brother’s literary prowess.

Indeed, in “Valium,” Ian transforms the mundane life of the speaker, whose “touch and go” happiness is as fleeting and insubstantial as the channel surfing he does in a “motel on the border of Utah and Colorado,” into a commentary on “the national consciousness.” Ian conveys what he refers to as “the tragic idealization of the American west” that the US public uncritically consumes through John Wayne and Annie Oakley clips, and which elide the violence of colonial legacies. With a little help from the rest of the band’s incantations and the mournful sound of the pedal steel guitar, a feature that permeates the album and gives it a beautifully haunting quality that leaves one wanting to join in with howls, the song ultimately revives the souls of those former inhabitants of Colorado and Utah in the midst of the speaker’s preoccupation with his own “warmly beating heart.”

James too shines on From Dreams to Dustwith “All the Way Down,” a song that focuses on artificial intelligence and, as he puts it, the transformation “from dust (or starlight) into something that can dream” and “Silverfish,” a piece that lists the external forces encroaching upon the speaker’s physical and social space, displacing him and unraveling his life as he helplessly repeats “I gotta to do something.”

While the band has recorded previous albums in studios, they also have a tradition of leaving the comforts (and restrictions) of the studio to record their music in unconventional spaces. Their first album was recorded in a leaking old theater in New York. This was the place where James learned to record. “It was awesome,” says James, adding that the band recorded the self-titled album The Felice Brothers in an old chicken coop. If we take James’ words from “Blow Him Apart,” James also “learned to sing / In a chicken coop,” a fact that speaks to The Felice Brothers’ embrace of their working-class roots and their commitment to remain raw, to merge the sacred simplicity of their recording process with the sophistication of their lyrics and musical sound. As Rolling Stone notes, “the band has, from its inception, prioritized self-definition” and, I would add, creative freedom.

“I’d rather be in a space where there is no time limit and if you break anything, it’s no big deal,” says James, whose tenure with The Felice Brothers has included many raucous performances. In the earlier years, until such an approach led to much broken equipment, The Felice Brothers invited audiences to join them onstage, and they have been known to have fans break out into impromptu performances in their live shows. These different manifestations of The Felice Brothers say as much about their humility as artists as it does their artistic principles.

“I want to continue recording in strange places that feel like home, that feel like ourselves,” continues James. The Felice Brothers have found their new recording home in an 1873 church that Ian renovated. Though the church had fallen into disrepair, Ian admits it was always his dream to use it. Feeling lucky to have acquired the property, Ian spent a few months renovating the approximately 30x40, one-room church. He put in new flooring, and The Felice Brothers would go on to record From Dreams to Dust in this new, old, and now hallowed, place. Considering the band’s history in unconventional spaces and the pandemic they have weathered apart, the renovated church represents Ian’s, and The Felice Brothers’, enduring commitment to friendship and music and to finding beauty, and hope, in unexpected places.

The restored church, like From Dreams to Dust, also reflects the Felice Brother’s unrelenting efforts to continue rebuilding in the wake of life’s decomposing cycles. Though perennially conscious of life’s treachery and our troubling ecologies, which we seem, as James remarks, “so ill-fitted to interact with,” The Felice Brothers constantly remind us that life’s mysteries are still worth pondering and, in so doing, offer us the blueprint for helping rebuild our lives after they collapse. As James sings in “All the Way Down,” whether we are “the union / Of an ape in an Apron/And a break in the clouds” or “nothing but starlight / All the way down,” we are alive and inhabiting this strange space together. Ian’s poetic final song, “We Shall Live Again,” assures us that even “in this life where any joyful thing / is paid two fold in suffering / we shall live again.” The phrase Dreams to Dust, then, may represent the deterioration of some hopes such as in the case of the two characters in “Inferno” who are consumed by the fires in a “fevered dream” and decaying lives as “some die on the steppes of frozen wasteland” while yet others “OD on the roads to Graceland” in “We Shall Live Again,” but, Dreams to Dustalso offers us the sacred ashes with which we might enrich the earth by scattering. That is, the Felice Brothers bequeath us the matter with which we might cultivate life and teach us the words, like chants, that offer the power to heal.

Written by: Geovani Ramírez

Band: The Felice Brothers

Album: Undress

VÖ: 03.05.2019

Label: Yep Roc Records / Bertus Musikvertrieb GmbH

Website: http://www.thefelicebrothers.com/

With ‘Undress,’ their first new album in three years, The Felice Brothers manage to walk that delicate tightrope between timely and timeless, crafting a collection that’s urgently relevant to the modern social and political landscape without ever losing sight of the larger picture. Offering moral clarity and sober reflection through nuanced character studies and artful parables, the band tips their caps to the biting wit of Mark Twain and the keen observation of Woody Guthrie here, presenting a series of portraits that mix the mundane and the fantastical in such a way as to blur the line between reality and metaphor: a man tosses all of his possessions into a smoldering crater; a White House spokeswoman stands naked before the nation; a small town kid turns to crime when his neighbors forsake him. In the world of The Felice Brothers, the traditionally powerful—politicians, preachers, pundits—are comical at best, rendered impotent by their own narcissistic ambition, while those who traffic in kindness and generosity are larger-than-life heroes, cast as everyday saviors walking the streets of a thankless society. In that sense, ‘Undress’ fits neatly into a long tradition of American folk storytelling, embracing what came before it even as it offers its own unique 21st Century twists along the way.

“Folk music has been a part of every era in American history,” says guitarist/singer/songwriter Ian Felice. “When you work within that folk idiom to tell a story about the human condition, you can hopefully end up with something that feels classic and current all at once.”

While ‘Undress’ contains many of the musical hallmarks The Felice Brothers have come to be known for since first emerging from New York’s Hudson Valley more than a decade ago (ragged guitars, weighty lyrics, a Replacements-esque sense that the wheels might come off at any moment), the record marks something of a new chapter for the group after undergoing major personal and professional changes. During the break between albums, Ian became a father and released both his first solo record and his first book of poetry, while new bassist Jesske Hume (Conor Oberst, Jade Bird) joined drummer Will Lawrence in rounding out the rhythm section following the departure of two longtime members.

“Jess and Will make for a truly solid rhythm section, and having that kind of strength really frees up Ian and me onstage every night,” says James Felice, who plays keyboards and accordion in addition to sharing writing and vocal duties with his brother. “There’s nothing quite like the feeling of being completely supported by great musicians.”

Support—musical, emotional, familial—has been at the heart of The Felice Brothers from the very start. Inspired as much by Hart Crane and Walt Whitman as Pete Seeger and Chuck Berry, the band first began performing on subway platforms and sidewalks in New York City in 2006. Within just a few years, they were playing Radio City Music Hall with Bright Eyes and appearing everywhere from the Newport Folk Festival to Levon Helm’s Midnight Ramble. They’d go on to release a series of critically acclaimed albums that pushed the boundaries of modern folk, with The New York Times likening their music to “the rootsy mysticism of the Band” and The Guardian hailing their songs as “impeccably crafted, with literary-minded lyrics that are both playful and profound.” The band shared bills with Old Crow Medicine Show and Mumford & Sons among others, took their blistering live show to Coachella, Bonnaroo, Outside Lands, and countless other festivals across the US and Europe, and backed up Conor Oberst extensively in the studio and on the road.

For a perpetually touring band like The Felice Brothers, the stage is an essential barometer for any new material, so before recording a single note of ‘Undress,’ they packed up their van and took the songs out for a three-week test drive.

“A bunch of revelations happen when you start to play a song live,” explains Ian. “It’s really important way for us to figure out what works and what doesn’t.”

By the time they headed into the studio in upstate New York, they’d locked in arrangements and culled their pool of 30 new songs down to a still-ambitious 20. Recording live to tape with producer/engineer Jeremy Backofen (Frightened Rabbit, Ólöf Arnalds), songs were generally captured in three or four takes, with raw, loose performances that emphasized vocal harmonies more than ever before.

“We just played all day every day for about two weeks in the studio,” says James. “We’ve worked with Jeremy in the past, and he’s a great architect and boss for us. He let’s us do what we want, but he pays really close attention to performance and has such a good ear for feel.”

‘Undress’ opens with the sardonic title track, a tightly grooving stream-of-consciousness that strips away the façades of money and power to confront the ugliness underneath. “Republicans and Democrats undress / Even the evangelicals, yeah you lighten up, undress,” Ian sings, juxtaposing “Caesars of wall street” and “trigger happy deputies” with Native American genocide and nuclear winter. Politics weighs heavily on the album, but it’s often tackled from surrealistic perspective that highlights the absurdity of it all. The Jack Spicer-inspired “Socrates” finds a songwriter sentenced to death for questioning a tyrannical government, while the cutting “Special Announcement” sees its narrator “saving up my money to be president.”

Dark as its depiction of the halls of government may be, ‘Undress’ ultimately believes in the inherent goodness of mankind, chalking our failings up not to malice but rather to being victims of a system rigged against us going all the way back to Adam and Eve. Over waltzing pedal steel on “The Kid,” Ian contemplates our own complicity in the wrongdoing of those we turn our backs on, while the banjo-driven “Hometown Hero” finds a petty criminal daydreaming of the parade that awaits his release from prison, and the tender “Poor Blind Birds” depicts humanity as helpless, innocent, fumbling for survival. It’s perhaps the infectious “Salvation Army Girl,” though, that offers the most hope for the future.

“I wanted a song about a female superhero,” explains Ian, “one whose superpower is charity.”

In his stark 1982 masterpiece “Nebraska,” Bruce Springsteen concluded, “I guess there’s just a meanness in this world.” The Felice Brothers might not disagree, but with ‘Undress,’ they’d like to remind you that there’s a kindness, too.

Infos zum vorherigen Album:

Band: The Felice Brothers

Album: Life in the Dark

VÖ: 24.06.2016

Label: Yep Roc / H’Art

Website: www.thefelicebrothers.com

The Felice Brothers’ new album Life in the Dark, due June 24 on Yep Roc, is classic American music. At once plainspoken and deeply literate, the band’s latest features nine new songs that capture the hopes and fears, the yearning and resignation, of a rootless, restless nation at a time of change.

Life in the Dark also coincides with the Felice Brothers’ 10th anniversary as a band. Hailed by the AV Club for a sound at once “timeless, yet tossed-off,” they’ve released plenty of music over the past decade, often on their own without a record label, but the new album is the fullest realization yet of the band’s DIY tendencies. Self-produced by the musicians and engineered by James Felice (who also contributed accordion, keyboards and vocals), the Felice Brothers made Life in the Dark themselves in a garage on a farm in upstate New York, observed only by audience of poultry.

“The recording is definitely rough around the edges and cheap,” James Felice says, laughing. “It was liberating and really cool to do. It allowed us to untether ourselves from anything and just make music.”

Because of makeshift studio set-up, the music they made was necessarily stripped down, emphasizing acoustic instruments and spacious arrangements on songs that showcase the sound of a band playing together live, with echoes in the music of Woody Guthrie, Townes Van Zandt, John Prine and rural blues.

“We tried to make it as simple and folk-based as possible, because we were working with limited resources,” singer and guitarist Ian Felice says. “We wanted to take all the frills out and make it just meat and potatoes.”

Still, there are hints of seasoning: among the folk and blues touchstones, the band took a certain inspiration from Neil Young and the Meat Puppets, too. Ian Felice says he was trying to channel the spirit of Meat Puppets II on opener “Aerosol Ball” — “They played kind of weird, freaky folk music, so there’s a connection there,” he says — while James Felice says listening to Neil Young’s Tonight’s the Night was like getting permission to make Life in the Dark.

“If you listen to that record, it’s fucking crazy,” he says. “We listened to that to know that what we were doing was legal and had precedent. If Neil Young could make a record that sounds like that, we can make a record that sounds like this.”

He’s referring to the wild, whirling accordion and big, loose rhythm on “Aerosol Ball,” mournful glimmers of electric guitar and fiddle on “Triumph ’73” and the ramshackle, blues-rock feel of “Plunder,” full of grainy lead guitars, blasts of organ and a shout-along chorus inspired by the rhythm of Shakespeare’s “Double, double toil and trouble” incantation in Macbeth. Though the Felice Brothers often share songwriting duties, the band gravitated toward Ian Felice’s songs for Life in the Dark.

Along with Shakespeare and the Meat Puppets, Ian Felice absorbed the essence of writers from Anne Sexton to Anne Frank, Raymond Carver to Dr. Seuss, on tunes with clear, if unintentional, political undertones. “It’s just what was going on when I was writing the songs,” Ian Felice says. “It’s a pretty politically charged climate right now.” To say the least.

The singer’s characters on “Aerosol Ball” exist in a dystopian culture bought, and ruled, by corporations; while “Jack at the Asylum” catalogs cultural ills including climate change, economic inequality and the numbing aspects of televised warfare, themes that recur again on “Plunder.” He wrote the title track after re-reading The Diary of a Young Girl, the journal that Frank kept while in hiding from the Nazis during World War II. “The idea of living in a dark attic unable to fully grasp what is going on in your life and feeling powerless to change it seemed like a relevant metaphor for me at the time,” Ian Felice says.

Elsewhere, he offers his own interpretation of classic American archetypes: “Triumph ’73” follows a young man on the cusp of adulthood desperate to ride his motorcycle away from the life changes overtaking him, while the ballad “Diamond Bell” tells the story of a folk heroine gunslinger in the vein of Pretty Boy Floyd or Jesse James, and the hapless, lovestruck kid she ensnares. “It’s part-love song, part-adventure story, part-tragedy, told in the Mexican folk tradition of singing about bandits,” Ian Felice says. “I think it’s one of the most straight-ahead narratives I’ve written.”

The band, also including Josh Rawson on bass and Greg Farley on fiddle, with drums by David Estabrook, spent about a month recording Life in the Dark in the late winter of 2015. James Felice learned engineering on the fly — “I literally had a book, like, ‘Where do you put the mic? How do you mic the kick drum?’” he says — and the band managed to nail most of the tunes within a few takes.

“There wasn’t too much agonizing, just the joy of playing music,” James Felice says. “We had an audience of chickens, and an audience of each other, and we were just really enjoying making it.”

The resulting album is more than just classic American music — it’s a parable for modern America.